|

| McManamy family in San Diego Jan. 2019 |

The Trumped-up immigration “crisis” does not conform to reality either, as the largest numbers of migrants was in the 1970s. There have been reduced numbers since then. What is new is that larger numbers of families, not single men, have been coming north out of desperation, trying to avoid having to join the gangs, pay extortion money, or be killed. What is new is Trump’s effort to discourage further immigration by cruelly and illegally separating families and even losing family members permanently.

I will not spend time making the case that we all know, that US policy since the 1950s has successfully broken any progressive governments in Central America, leading to the breakdown of economic and political organizations in those countries and providing a vacuum into which gangs and drug cartels, fueled by demand for drugs in the US, have rushed, making life untenable for many in Central and South America.

I won’t review the fact that US law allows for people to legally request asylum, presenting themselves ANYWHERE at that country’s border, and making a case that they have a credible fear of persecution in their country and cannot return.

Instead, I’ll focus on providing a first-hand account of my experiences at the border. We

were lucky to spend a week’s vacation there: John (medical experience), Evan and Laura (Spanish, and Laura had lots of background working with immigrants already) and me (Spanish, French and Creole language experience). We each gravitated to the organization that seemed most appropriate to us. Some prepared food at World Central Kitchen, some provided emotional support to migrants through the temporary Sanctuary Caravan, and I focused on legal (and emotional) support at Al Otro Lado. Its name means “to the other side”. It is a very impressive non-profit that has been working since 2012 offering legal support to migrants. They have been open every day since Thanksgiving. In that time period they have completed 1200 private consultations, currently running a daily workshop, with 30 - 50 volunteers per day.

were lucky to spend a week’s vacation there: John (medical experience), Evan and Laura (Spanish, and Laura had lots of background working with immigrants already) and me (Spanish, French and Creole language experience). We each gravitated to the organization that seemed most appropriate to us. Some prepared food at World Central Kitchen, some provided emotional support to migrants through the temporary Sanctuary Caravan, and I focused on legal (and emotional) support at Al Otro Lado. Its name means “to the other side”. It is a very impressive non-profit that has been working since 2012 offering legal support to migrants. They have been open every day since Thanksgiving. In that time period they have completed 1200 private consultations, currently running a daily workshop, with 30 - 50 volunteers per day.

Not being a lawyer, I wondered at first how I would be able to be of assistance through this organization whose main mission is helping migrants prepare for their Credible Fear Interview with an ICE judge. This is the first hurdle that migrants must pass in order to be allowed to request legal status as refugees.

I should not have worried. The goal of the work is to help migrants represent themselves at the border. Surprise: no lawyers are provided. Many lose their documents or have them stolen or destroyed by rain. So they must be able to summarize their case, from memory, in this interview. An excellent curriculum has been created, with a mnemonic of a hand to remember the 5 points that must be made. My job, and that of most of the volunteers, was to help individual migrants organize their traumatic experiences and fears of future

persecution into a synopsis that they could present to the immigration judge.

Officially, I helped to plug a gap in the services for French-speaking and Haitian-Creole-speaking migrants. Unofficially, I helped to provide the “glue” frequently needed to keep a volunteer organization running. I roamed the building, bringing people to medical or legal areas, addressing new minor issues as they arose, and mostly being available to hold a hand, say a prayer when one was asked for, or simply listen.

Here are some pictures:

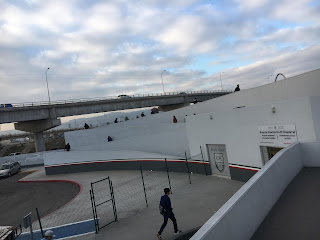

End of a long day at Al Otro Lado. Taken from the roof, a hub of activity all day long. This open area serves as spillover interview space. I generally brought migrants here for their introductory lecture about the process, the intake interview (basic demographic data) and credible fear interview preparation. It was easier to converse in French or Haitian Creole here than in the crowded Spanish classroom space below. I love the view across Tijuana to the mountains beyond. Behind me is the data room where cases are typed up every afternoon. They are then uploaded, along with photos of the person’s documents, to a private folder accessible only to the person and those whom they share it with (generally family members).

Entering via the pedestrian crossing.

Turning off our cell phones in case we were asked to share the contents.

Below, the enormous shopping mall on the US side of the border, seen from the pedestrian transit area.

Dawn – daily pedestrian commuters to the US.

Site of the awful tear gassing incident in December. People got tired of waiting (perhaps forever) and tried to cross the border at other than a “legal” point of entry. Remember that it is legal to cross anywhere to request refugee status. This is a river bed, also encampment sites under the bridges. When it rained for several days, it became a fast-flowing river. The inhabitants spent the rest of the week trying to dry out their belongings under the highway bridge.

For obvious reasons, very few pictures of migrants or volunteers.

This is the only one I took. It is a man from Honduras who was resting outside, waiting for interviews to begin for the day. He is wearing a woolen hat, one of a number that we found on sale nearby for $2 each and donated. It was cold last week in Tijuana.

We are working in an oppressive system that requires people to relive trauma they have experienced, over and over, in order to receive protection in the US. Some trauma was experienced at home, and was the impetus for leaving. Other trauma occurred nightly in Tijuana. Not just young men, but middle-aged women and older couples report being threatened or robbed in the city. They come in each morning with fresh injuries and fearful stories.

As one of the few French speakers available last week, I worked with a large number of Africans and Haitians. However, the largest numbers of migrants were from Central America, and especially from the Northern Triangle where drug cartels have nearly overshadowed the governments: El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. One way for me to process this experience, and to honor the people who have been forced to face this journey, is to tell some of their stories. I hope you will join me in holding these individuals in your prayers, in the Light, or in whatever way you choose to remember that our fellow humans are going through this hell. As Luis, one of the leaders at Al Otro Lado, said, “We run off anger and love here.”

Some stories:

The very first day, as John and I arrived at Al Otro Lado, a woman was brought in by a volunteer from another non-profit. A middle-aged woman traveling alone from Honduras, she had no place to stay the night before and nothing to eat. She had knocked on a door and been allowed to sleep on someone’s floor, wearing her sweatshirt but with no bedding. She was a diabetic, and her first complaint was that she might be having an insulin reaction. We brought her to the medical clinic area and her story spilled out of her. She had not taken her insulin medicine because she lost her pocketbook. She lost it when she grabbed the wrong bag while escaping from thieves who had held a gun to her head. They had tied her up and she was finally able to escape. She quaked and cried as she repeated her story over and over. This was our first experience at Al Otro Lado, before we got a chance to take the volunteer training.

This often happened. A piece of the story would come out, followed by another and another. Emotional trauma makes it harder to order one’s problems. And in fact, the diabetes WAS the biggest problem of the moment. Until I sat down with her and held her hand, at which point I heard the bigger problem. As to why she left home in the first place, we didn’t even get to that.

Her medical crisis over, she was invited to take a nap on the couch in the sunshine. It was warm and quiet there. When she awoke, she told me that she believed in God and that God would take care of her. I sensed that she wanted to pray, and we prayed together, my mind expanding into the verbal prayer that is foreign to me but seemed to be comforting to both of us, praying aloud in duet form.

Two sisters from a small town in El Salvador whose family had a small business. Because they were unable to pay extortion demands from the gangs, three family members were killed. They posted notices around town and sought help from the police to find their niece’s body but received no help or information. They had to abandon the business and head north.

J., a young man from Honduras who lived with his parents and was attending university. His brother had been forced to join a gang and when he was put in jail for his activities, he was forced to continue to provide services for the gang from prison. Eventually he was killed by the gang. J. and his parents were forced to leave their home which they owned and flee to another city, where they rented another home they could not afford. J. had to leave university to support his family. He was attacked and threatened by a gang member with a machete when he went to secure his house.

G., a political prisoner from Central African Republic. He fled, leaving his wife and two children in hiding. He reminded his fellow migrants to ask the immigration officer for asylum without fear, as it is his right. He suggested avoiding looking at the officer in the eyes but to look elsewhere so as to claim his story and not to lose his nerve.

A 21-year old man I met in the medical clinic was very cold, shaking. He was traveling alone, and said he could trust no one. We found him a hat and helped him to change into donated dry socks and boots. He told me he was looking for a job as a cook in Tijuana. I sat down with him and helped him with a to-do list, to work towards this seemingly impossible task.

Every single one of the migrants I met had experienced, and were experiencing, trauma. I asked people “How are you doing?” and immediately I saw tears spring to their eyes. They opened up to me, telling me their case. Why were they so willing to trust, having been hurt so much? I think it is because people crave community, they need love more than anything else.

Guarded faces collapse into tears when a hand is held, a smile is offered. A couple from Africa was stony-faced until I showed them the bulletin board that offered “Welcome!” in many languages. I asked them to write it in their language, Wolof. They smiled and carefully wrote on the board, “Dendale”. Then they began to trust me with their story. Sitting on the roof overlooking Tijuana to the south and San Diego to the north, they told me their experience of racism, forced marriage and death threats from a brother. We worked together to order the facts into a coherent, true story that even a border crossing guard might recognize as worthy.

Some people hold their stories tightly, not ready to share their pain with me. Two men from Haiti are traveling together, and I describe how it might be that certain categories of people receive protection under US law. I mention protected classes including race, nationality, religion and social groupings such as homosexuality. In hearing the process they were likely to experience if they decided to try to cross the border and ask for asylum, one of the two progressively lost his energy and finally leaned back on the couch, almost asleep. Is he tired, sick or just discouraged? His partner seemed ready to cope, mentioning a friend in the US and a ready understanding of the requirement to prove their need to enter the US for safety. I provide the best information we have as to the trip ahead, and I can see him and his partner weighing silently the risks of going ahead or staying back. I tell them that they will likely be separated from each other at the border.

Those from Central America mostly reported suffering from gangs, threats, cartels stronger than governments. The Africans are more likely to report government corruption: abductions, being thrown in jail with no trial, torture. We can offer the hand of friendship, support and some information, of unknown reliability, of the path ahead. “If you make it past the first interview, you will be put in a cold detention center for an unknown period, allowed to keep only one layer of clothes.” Is this true? We don’t know, but that’s what we hear. Single men are often detained for long periods, while families might be dropped off before midnight at a McDonalds in San Diego.

Knowledge is spotty among both volunteers and migrants. I asked a woman from Africa who had traveled up from Brazil, “Did you come to join the caravan?” “What caravan?” she asked. We volunteers know little about the shadowy organization of the number system, “the list”, by which households are chosen to cross the border. It was apparently created by a group of Haitian migrants in 2016, and is now managed by an organization connected with the Mexican police. It makes sense, to avoid a riot. Even so, migrants wait 6 to 8 weeks at the border, trying to stay safe and warm while checking at the desk frequently to make sure they do not miss the call. Once they are called, they are put in a bus and driven to the automobile crossing, a couple of miles away.

Waiting for the bus is agonizing. Evan and Laura befriended a family with two children and spent the morning offering piggy back rides, and otherwise entertaining the children so the parents could have a few moments’ peace. Later, Laura received information via Facebook that the family had been released and were headed north to their sponsor family member, someone with papers living in the US. Evan did some research on ICE records and found that a woman he had worked with was in detention. These are the only people we were able to receive information about on the other side.

The list is a shadowy project: volunteers and most of all, migrants are governed by it, yet to participate in it is an acquiescence to an unfair, cruel system. An unpredictable number of families is called each day; the number is much smaller than the need and seems intended to discourage those seeking immigration. Volunteers from Al Otro Lado observe the process every day and report back the important facts: how many numbers are called, who is separated and who is allowed to travel together, what is the final number reached each day. If a household is not present on the day their number is called, they may have to start again with a new number. Maybe there will be a second chance for those who missed their number. Or maybe not, as those who are present each day complain that others are given two chances and they are given none.

Similar to the capricious information at the Tijuana border, the border fencing is made up of many different structures cobbled together. A three-story building topped with accordion wire like a jail. A huge spiral staircase outdoors, an open-air zig zag stair on the other side. A chance to be seen and evaluated by the cameras everywhere. A labyrinth of one-way doors, hallways, new and old together. Rules change every day. One minute no line for pedestrians to cross, then the next minute there are 20 on line as a new form must be filled out. We are in a stream of travelers, most of whom seem to make this transit daily to go to work. We are among the lucky ones with permission to cross the border at will.

So many people are committed to this work. It was an honor to be among them for a few days. Here I am in front of the office of Deported US Veterans. There are reported to be

about 3000 deported US veterans in other countries in total. The man running the office had raised a family in the US after serving in the military. A dozen years ago, he was picked up on a minor marijuana violation and deported. He says he will be welcome to go back only in a coffin, when he will be buried with full military honors.

Too bad this story does not end on a happier note.